What the New Ugly Says About Design Right Now

- Nathanael Lim

- Jan 2

- 6 min read

As the year draws to a close, I have had the luxury of stepping back to reflect on our output in 2025 and, more importantly, to consider where experimentation might lead us next. One that has stayed with me is how design practice in Asia might continue to develop without defaulting to Eurocentric frameworks.

That curiosity led me, somewhat unexpectedly, down a rabbit hole surrounding the New Ugly, often discussed in Chinese design discourse as 新丑风. The more I encountered the term, the clearer it became that this was not a single style or movement, but a recurring attempt to name a discomfort with polish, refinement, and the quiet authority of modernist systems.

This article is not an attempt to offer a definitive explanation of what the New Ugly is. Many designers and writers are far more qualified to do so, and many already have. Instead, this piece functions as a way for me to think aloud. It is an effort to make sense of why this design language feels newly resonant, and how it sits alongside the principles that have shaped my own practice.

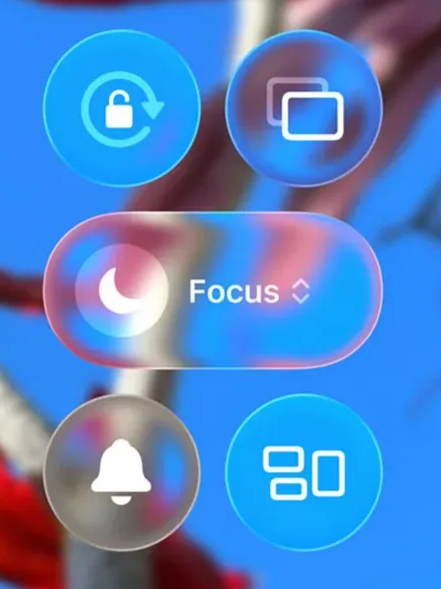

The renewed interest in the New Ugly reflects a broader desire to step away from sleek minimalism and toward a visual language that feels closer to an earlier, more optimistic moment. At the same time, this shift is not exceptional, nor does it sit outside prevailing neoliberal logic. Its circulation remains closely tied to capitalist conditions, as seen in moves such as Apple’s revival of Frutiger Aero through liquid glass aesthetics. The apparent imperfections associated with the New Ugly often function as markers of human authorship, particularly at a moment when many AI systems still struggle with typography, let alone with producing intentional irregularity. What is being recognised here is not poor design, but the work of designers capable of producing low-control outcomes with a high degree of precision.

The essay unfolds in three parts. It’ll begin by situating the New Ugly through its common characteristics and its cultural context, with particular attention to how it reads within Chinese graphic design history. Then, examine its relationship with capitalism, as one that adapts to and circulates within. Finally, I consider how the New Ugly gains renewed relevance amid growing fatigue toward AI-generated visual output. The conclusion returns to Swiss Design, not as a framework to be defended or abandoned, but as one that gains clarity when placed in tension with the New Ugly.

What is The New Ugly?

The New Ugly describes a contemporary approach to graphic design where visual tension is the result of conscious choice hidden as oversight. It is most often recognised through crowded compositions, uneasy hierarchies, and typographic decisions that resist easy resolution. These qualities can initially read as rough or unfinished, yet they are better understood as evidence of a designer deciding where to stop rather than how far to refine.

What matters here is the designer’s intent, where many of the so-called mistakes associated with the New Ugly operate as traces of judgement. Spacing that refuses consistency or layouts that avoid balance suggest that correction was possible and deliberately withheld.

This way of working becomes more legible when placed outside a Western account of graphic design that centres modernism and industrial production as its starting point. As Jiarui Wang observes, such narratives tend to narrow the definition of graphic design, overlooking the long history of ordering, marking, writing, and making that exists across cultures. Design did not begin with modernist systems, nor does it belong to a single lineage.

In the Chinese context, graphic design has long been shaped by negotiation between imported ideas and local ways of thinking. Influenced by Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, Chinese art has historically favoured harmony, symbolism, and restraint. Against this background, disruption becomes legible as an intentional break rather than an aesthetic accident.

At its core, the New Ugly is concerned with making decision making visible, allowing traces of authorship to remain. What emerges is not bad design, but a different understanding of control, one that is felt through tension.

What is the relationship between the New Ugly and capitalism?

The New Ugly is often framed as resistance positioned against minimalism and Corporate Memphis. At first glance, that interpretation is appealing, but it's incomplete. Rather than standing outside capitalism, the New Ugly operates comfortably within it, shaped by the same pressures that favoured minimalism before it.

As markets mature, visual sameness becomes a problem. Systems designed for scalability tend to converge, especially when success leaves behind best practices that are furiously replicated. In this context, the appeal of the New Ugly lies less in its oppositional stance and more in its ability to reintroduce distinction where refinement has become the norm.

Capitalism does not require beauty so much as differentiation. When minimalism reached the point where it signalled competence rather than ambition, its communicative power weakened. The New Ugly fills that gap by offering friction in place of mass appeal, its visual tension reads as evidence of choice, and choice continues to function as a marker of value.

Even when the New Ugly is taken up by large organisations, it is rarely adopted in full. Elements of disruption are introduced selectively, kept within brand guidelines and commercial constraints. Apple’s recent use of liquid glass aesthetics, alongside renewed online fascination with Frutiger Aero, is a useful example. What appears as a return to visual complexity is tightly managed, drawing on nostalgia and texture without abandoning control. In this sense, the New Ugly reflects capitalism’s capacity to absorb critique and convert it into surface distinction.

How the New Ugly Pushes Back on AI-Generated Slop

The renewed interest in the New Ugly coincides with a growing fatigue toward AI-generated visual output. Many viewers already approach machine-made design with scepticism, and this suspicion often attaches itself to work that feels overly resolved. In this context, intentional misperfection has begun to function as a marker of human authorship.

The New Ugly becomes legible here not because it looks rough, but because it makes decision making visible. This quality stands in contrast to how generative systems operate. Most models are built to converge toward probable outcomes. There is little incentive to stop short or to favour an awkward solution over a favoured one once a preference has been established. In other words, AI has no reason to design in ways that appear ugly, because ugliness rarely improves predictability. The New Ugly, by contrast, relies on judgement exercised against that impulse. What looks inconsistent on the surface often follows a clear internal logic shaped by intent.

Justin Zhuang’s discussion of Darius Ou’s work offers a useful insight. In one project, Ou avoided bold text as a conventional tool for hierarchy. Instead, the copy gradually increased in weight across the composition to reflect the idea of evolution. The approach required careful control, as the change had to remain perceptible without tipping into confusion. The experiment lay not in breaking rules indiscriminately, but in selecting which rule to bend and designing a structure that could support that deviation.

The New Ugly does not operate through randomness or error, instead it depends on structured experimentation and an understanding of design systems deep enough to be manipulated without collapse. As generative tools continue to improve at producing competent layouts, this kind of judgement becomes easier to recognise. What persists in the New Ugly is not resistance for its own sake, but a visible record of choice, one that remains difficult to automate away.

My interest in the New Ugly has forced me to look again at Swiss Design, not as a canon to defend or discard, but as a system whose assumptions deserve renewed scrutiny when applied beyond its original context. The question is no longer whether one approach replaces the other, but how the tension between them sharpens our judgement as designers working today.

Grids, typographic order, and repeatable logic allowed design to scale with clarity and discipline. The New Ugly interrupts that inheritance by insisting that systems are not endpoints. Intervention becomes a legitimate act once the system has done its work. In this tension between system and intervention, design shifts from execution to authorship. A similar recalibration appears in the movement away from neutrality. The New Ugly accepts that neutrality is rarely neutral in practice, especially once design circulates across cultures, economies, and power structures.

For designers working in Asia, these tensions feel especially relevant. Much of our education remains grounded in Eurocentric models that privilege order, neutrality, and universality. The New Ugly offers less a style to adopt than a way to question which values we inherit by default and which we choose to carry forward.